I went to volunteer at the museum where I used to intern on Sunday.

It was really cool to arrive and to see some Jewish guys in the lobby. Though the museum is a historically Jewish, it doesn't attract the masses of Orthodox Jews it should as a great place for families to visit. It especially doesn't attract young adults on a Sunday morning.

One of the guys was a lanky giant, over six feet tall with overgrown hair and peyot (side locks). Another had a beard but no peyot. All three were wearing yalmulkas and tzitzit. I was super excited to see orthodox Jews my age taking an interest in something I feel passionate about.

A few minutes later, the Director of Visitor Services started chatting with them and I realized they weren't there for a tour. They were a band scoping out a location for a music video. #disappointed #zusha #neverheardofthem

On the Germany Close Up program this summer, two of the participants were students of history so I know history is not lost art. However, Orthodox Jews, particularly Chasidic Jews, have a different American history than other Jews. The museum celebrates Jewish American culture, a lot of which is not part of the Chassidic heritage. I wonder if that accounts for the dearth of Orthodox visitors.

Chassidish Jews did not generally partake in Yiddish theatre nor read American Jewish literature that shaped the culture of secular Jews today. The Jewish culture that the museum celebrates does not always transfer to chassidish history.

Chassidic culture emphasis oral history. I did not realize until I was older and waiting on line for Moth events to hear people tell stories how much it had been a part of my upbringing and education. Speakers at our school would tell stories about their lives as emissaries of the Chabad Rebbe. The stories usually had a lesson. The oral history happened at farbrengen and dinner tables. Growing up, I heard tales of Chassidic masters spanning the centuries and anecdotes of their disciples. These stories nurtured my identity and gave me an understanding of where I come from.

There is a fascinating discussion by a psychologists on how family narratives lend to identity and how they boost self confidence to withstand challenges. Telling family stories to children is not just about moral lessons, it is also armor. This idea is immensely powerful and there is a museum in Israel encouraging families to share that story

These narratives also lent itself to developing my love of history even for history that is not wholly my own as it shows how society was shaped and can even predict where society will go. The museum hosts as lot of culturally American-Jewish events. Klezmer music, Yiddish theatre and the like however that is not my family history nor the history of the Chassidism. Regardless, it shapes where we are today.

An orthodox synagogue in my neighborhood is doing klezmer nights though it is culturally Jewish. We share each others history. All branches of Judaism collectively make up where we stand today. Learning each other's history may allow us to understand each other better. Come visit the museum some time.

Happy Chanukah!

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Sunday, December 7, 2014

At what point will Chabad not be Chassidishe?

I had a discussion about modern orthodox with a Rabbi who works for the OU. He said something about Chabad being considered modern to the chassidishe communities in Borough Park and Williamsburg. I was slightly affronted but it was also something I had not considered before. Other than the knowledge that tznuis manifests itself differently, I did not have a lot of interactions with those communities.

Last Shabbos, someone asked me what Chabad is. Technically, it is a type of chassidus. What chabad is as a movement is another story. The sects from Borough Park, Williamsburg and Crown Heights are all chassidish. The mystery: how does this common denominator translate to daily life? And does Chabad share the implications in their daily conduct?

Chassidus philosophy was first taught to the average man by the Baal Shem Tov in the year 5490 (1730). After his passing on the first day of Shavuot of 5520 (1760), his disciple the Maggid of Mezeritch took over until his passing on the 19th day of Kislev 5533 (1772). At this point the Chassidic movement was split between three of his students. (Read more here, subtitle Spread of Hasidism). At this point the different sects developed.

During another discussion, the same Rabbi from the OU said something to the effect that Maimonides in Moreh Nevuchim, third chelek, section 18 claims that hashgacha protis is proportionate to spiritual level. This in contradiction to the teaching of the Baal Shem Tov. There is a famous story of the Baal Shem Tov, when he was walking with his students and pointed out a leaf floating softly to the ground. He asked his students what caused this to happen. It was not the wind, but G-d who directed the leaf to fall precisely so to shade a worm from the blazing sun. Chassidim believe in Divine Providence in the inanimate object as much as the spiritual being.

How to resolve this? I asked my Bobov coworker who knew the story and said her understanding of Hashgacha Protis went according to the Baal Shem Tov. The point of this essay is to discover commonality between my community and hers and this confirmed we have the same root philosophy. For the answer to the conundrum, see Chapter 2 of the book Led By G-d's Hand.

What are traditions we share?

My chassidish co-worker met her husband three times before they became engaged. Once at her house, once at his house and once at the home of her grandmother. Some chabad couples date very little. However they still go out on dates. Then again, some chabad couples date for a few months or even a year.

My Satmar co-worker had a nine month engagement. In Chabad, the average engagement is two to three months. If it is more it is usually because Chabad custom is not to marry during the Omar weeks between Pesach and Shavout.

The Rebbe encouraged the idea that the prospective bride and groom should not be in the same town during the engagement and should not spend an excessive amount of time together. My Satmar co-worker chatted with her husband once every three weeks! Her husband spoke to her dad weekly to wish her family a good Shabbos. More chassidish Chabad adheres to this idea and meet at Shabbos meals or meet up for wedding preparations. Most Chabad couples hang out frequently during the engagment

There is also a shared tradition not to be photographed together during the engagement. Both get around this by taking un-posed pictures. Today, it is a normal practice for Chabad families to hire a photographer for the engagement party.

All this makes Chabad another variant on the chassidishe lifestyle. However, the things that make Chabad chassidish, outside of its philosophy, are not widely recognized. The shared customs and traditions connect us and as we get lax about them we lose something of that shared heritage.

Last Shabbos, someone asked me what Chabad is. Technically, it is a type of chassidus. What chabad is as a movement is another story. The sects from Borough Park, Williamsburg and Crown Heights are all chassidish. The mystery: how does this common denominator translate to daily life? And does Chabad share the implications in their daily conduct?

Chassidus philosophy was first taught to the average man by the Baal Shem Tov in the year 5490 (1730). After his passing on the first day of Shavuot of 5520 (1760), his disciple the Maggid of Mezeritch took over until his passing on the 19th day of Kislev 5533 (1772). At this point the Chassidic movement was split between three of his students. (Read more here, subtitle Spread of Hasidism). At this point the different sects developed.

During another discussion, the same Rabbi from the OU said something to the effect that Maimonides in Moreh Nevuchim, third chelek, section 18 claims that hashgacha protis is proportionate to spiritual level. This in contradiction to the teaching of the Baal Shem Tov. There is a famous story of the Baal Shem Tov, when he was walking with his students and pointed out a leaf floating softly to the ground. He asked his students what caused this to happen. It was not the wind, but G-d who directed the leaf to fall precisely so to shade a worm from the blazing sun. Chassidim believe in Divine Providence in the inanimate object as much as the spiritual being.

How to resolve this? I asked my Bobov coworker who knew the story and said her understanding of Hashgacha Protis went according to the Baal Shem Tov. The point of this essay is to discover commonality between my community and hers and this confirmed we have the same root philosophy. For the answer to the conundrum, see Chapter 2 of the book Led By G-d's Hand.

What are traditions we share?

My chassidish co-worker met her husband three times before they became engaged. Once at her house, once at his house and once at the home of her grandmother. Some chabad couples date very little. However they still go out on dates. Then again, some chabad couples date for a few months or even a year.

My Satmar co-worker had a nine month engagement. In Chabad, the average engagement is two to three months. If it is more it is usually because Chabad custom is not to marry during the Omar weeks between Pesach and Shavout.

The Rebbe encouraged the idea that the prospective bride and groom should not be in the same town during the engagement and should not spend an excessive amount of time together. My Satmar co-worker chatted with her husband once every three weeks! Her husband spoke to her dad weekly to wish her family a good Shabbos. More chassidish Chabad adheres to this idea and meet at Shabbos meals or meet up for wedding preparations. Most Chabad couples hang out frequently during the engagment

There is also a shared tradition not to be photographed together during the engagement. Both get around this by taking un-posed pictures. Today, it is a normal practice for Chabad families to hire a photographer for the engagement party.

All this makes Chabad another variant on the chassidishe lifestyle. However, the things that make Chabad chassidish, outside of its philosophy, are not widely recognized. The shared customs and traditions connect us and as we get lax about them we lose something of that shared heritage.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Girl On Telucha

It started off as a much needed walk after all the holiday meals and a good preparation for the festivities of Simchat Torah. Just before we reached Prospect Park, my friend and I realized last year we had taken a walk on Sukkot and had meandered into the historic Kol Israel Synagogue.

This reminded me that I had always wanted to see the Eldirdge Street Synagogue in action. After a should we, dare we, why not conversation we went along Flatbush Avenue and then onto the Manhattan Bridge for a five mile walk to Eldridge Street. At long last we reached the majestic building. I was so anticipating the joy of Torah in the space where Jews have celebrated for a hundred years. The gate was open but the doors were locked! I knocked and then my friend pounded the doors so hard I thought the alarm would go off. All this way for naught.

We were determined to see a shul at this point. Any really. I knew further into the Lower East Side there would be more synagogues but I did not know where. We stopped by the fire station for directions. When we saw the Chabad boys behind us so we knew we were going the right way. Until they turned someplace far back and we were lost again.

Chabad chassidim, men anyway, go on telucha on Sukkos. I am not actually sure of what the exact definition of the Hebrew word is except that its source is in the word 'to go'. They go on long walks to increase the celebration in shuls all over. This year, my friend and I, unintentionally as it was, were joining the telucha march. I would say that we are uber chassidish.

After spotting Hebrew letters we tried the door of the first building we saw. That's when my friend read the sign and said we were breaking into the Chevra Kadisha. Whoops. We knew we had finally reached the right street by the myriad groups of Chabad boys milling in front. It was party time. At last I was going to see Shtiebel Row, a famous street on the LES leftover from days when all the streets were teeming with Jewish houses of prayer, and I was going to see it in action! Bounding up the steps we thought we had missed it but the upstairs congregation was still going strong. We must have looked exhausted because a woman offered us seltzer. Everyone was so welcoming without asking questions. Just welcome. No cross examination though they were probably a tad curious as to how a girl in sneakers and a girl dressed to the nines had wandered into their midst.

We stayed for an hakafa and then went to the next shul. There we were welcomed by a girl named Tikva who explained that the white curtain over the Aron was there just for the holiday season.

At our next stop, we tailgated on a chassidish man's Kiddush. We burst into the room with his back toward us but this mother said, "keep them in mind!" He turned around and nodded. They gave us cake and we chatted and she told us that Young Israel and Bialystocker Shul did a hakafa together in the street. We raced further down the block to see the street blocked off and people singing, dancing, rejoicing.

My friend met her high school principal whose father had been the Baal Tefilah at the Bialystocker Synagogue. She told us that it had previously been a church and a stop on the underground railroad. It is a breathtaking synagogue. It has stunning murals of the Jewish signs for each month on the ceiling.

We saw six shuls rejoicing that night. My favorite moment though was the boys who had participated in the outdoor hakafah. They danced backward in a row, arms thrown across each others shoulders as they faced the Sefar Torah. They escorted the Torah back into the shul while singing Lishana Haba BiYerushalayim.

Simchat Torah is a holiday in celebration of the Torah. We dance around the bima, reader's platform, with the Torah scrolls in hand. However it was in that moment, with the boys facing the Torah that I saw the love as well as the joy.

The Torah starts off with the letter Bet and ends with the letter Lamed. Spelling the Hebrew word "lev" which means heart. The Torah is the heart of the Jewish people. Watching those boys dance in honor of the Torah reminded me of how cherished it is and of how cherished we are.

The beautiful night did not end there. We still had our long trek home. This time we kept up with the amazing Chabad kids who come to the city, dance furiously, walk back to Crown Heights and then continue the celebration a 770.

The Israeli thirteen year olds, who come to spend Tirshria in Crown Heights, generally drive me crazy. However, they are also a lifeline of passion and fervor in what it means to have mesiras nefesh in the twenty first century. To save in order to scrape enough for a flight to New York. Then to attend classes and celebrate Tirshria in Crown Heights. To see the iconic shul they had only seen in videos. To celebrate in a space where their inspiring lessons stemmed from.

They're crazy but in a good way.

This reminded me that I had always wanted to see the Eldirdge Street Synagogue in action. After a should we, dare we, why not conversation we went along Flatbush Avenue and then onto the Manhattan Bridge for a five mile walk to Eldridge Street. At long last we reached the majestic building. I was so anticipating the joy of Torah in the space where Jews have celebrated for a hundred years. The gate was open but the doors were locked! I knocked and then my friend pounded the doors so hard I thought the alarm would go off. All this way for naught.

We were determined to see a shul at this point. Any really. I knew further into the Lower East Side there would be more synagogues but I did not know where. We stopped by the fire station for directions. When we saw the Chabad boys behind us so we knew we were going the right way. Until they turned someplace far back and we were lost again.

Chabad chassidim, men anyway, go on telucha on Sukkos. I am not actually sure of what the exact definition of the Hebrew word is except that its source is in the word 'to go'. They go on long walks to increase the celebration in shuls all over. This year, my friend and I, unintentionally as it was, were joining the telucha march. I would say that we are uber chassidish.

After spotting Hebrew letters we tried the door of the first building we saw. That's when my friend read the sign and said we were breaking into the Chevra Kadisha. Whoops. We knew we had finally reached the right street by the myriad groups of Chabad boys milling in front. It was party time. At last I was going to see Shtiebel Row, a famous street on the LES leftover from days when all the streets were teeming with Jewish houses of prayer, and I was going to see it in action! Bounding up the steps we thought we had missed it but the upstairs congregation was still going strong. We must have looked exhausted because a woman offered us seltzer. Everyone was so welcoming without asking questions. Just welcome. No cross examination though they were probably a tad curious as to how a girl in sneakers and a girl dressed to the nines had wandered into their midst.

We stayed for an hakafa and then went to the next shul. There we were welcomed by a girl named Tikva who explained that the white curtain over the Aron was there just for the holiday season.

At our next stop, we tailgated on a chassidish man's Kiddush. We burst into the room with his back toward us but this mother said, "keep them in mind!" He turned around and nodded. They gave us cake and we chatted and she told us that Young Israel and Bialystocker Shul did a hakafa together in the street. We raced further down the block to see the street blocked off and people singing, dancing, rejoicing.

My friend met her high school principal whose father had been the Baal Tefilah at the Bialystocker Synagogue. She told us that it had previously been a church and a stop on the underground railroad. It is a breathtaking synagogue. It has stunning murals of the Jewish signs for each month on the ceiling.

We saw six shuls rejoicing that night. My favorite moment though was the boys who had participated in the outdoor hakafah. They danced backward in a row, arms thrown across each others shoulders as they faced the Sefar Torah. They escorted the Torah back into the shul while singing Lishana Haba BiYerushalayim.

Simchat Torah is a holiday in celebration of the Torah. We dance around the bima, reader's platform, with the Torah scrolls in hand. However it was in that moment, with the boys facing the Torah that I saw the love as well as the joy.

The Torah starts off with the letter Bet and ends with the letter Lamed. Spelling the Hebrew word "lev" which means heart. The Torah is the heart of the Jewish people. Watching those boys dance in honor of the Torah reminded me of how cherished it is and of how cherished we are.

The beautiful night did not end there. We still had our long trek home. This time we kept up with the amazing Chabad kids who come to the city, dance furiously, walk back to Crown Heights and then continue the celebration a 770.

The Israeli thirteen year olds, who come to spend Tirshria in Crown Heights, generally drive me crazy. However, they are also a lifeline of passion and fervor in what it means to have mesiras nefesh in the twenty first century. To save in order to scrape enough for a flight to New York. Then to attend classes and celebrate Tirshria in Crown Heights. To see the iconic shul they had only seen in videos. To celebrate in a space where their inspiring lessons stemmed from.

They're crazy but in a good way.

Friday, October 3, 2014

A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Validations

In Germany, we went to the Reichsparteitagsgelände, the rallying grounds in Nuremberg. There, we took this photo:

The story behind the picture can be read here. We stood where we once could not. Where my great-great grandmother, who was murdered by Nazis, could not stand. We stood to say we are here.

In my pursuit to visit as many New York City museums as possible this year, I went to the Museum of Chinese Americans. It was largely about the history and culture of the Chinese in America and the challenges, including racism, they face(d). In the exhibit exploring the definition of what it means to be a Chinese immigrant or even a United States citizen this was displayed:

Does it remind you of anything? Perhaps something you saw in your grade school history book?

Take a look at this and see what you can remember:

The famed railway which, in 1869, united the contiguous United States. Look at the picture closely. There are no Chinese in the photo though there were over 12,000 Chinese and Chinese Americans who helped build it. Many who took on dangerous tasks in desperation for a few dollars.

So why did the photographer want to go back and take a picture there with Chinese Americans? What do we accomplish by these photos? We are obviously here. Why take on the expense for a mere photo? What are you communicating by doing this?

In an article, Mr. Corky, the photographer, asks for participants to come "reclaim a bit of Asian American history."

Maybe when we go somewhere and we study the history we also change it. Some say history is dead. Maybe it is alive. Or if it is dead it does not rest in peace. It haunts us continuously by playing an incredibly active role in shaping our lives today. How we respond to it changes its impact and thereby changes the status of the past. It puts an intense power into our hands.

Saturday, September 13, 2014

Meeting Germany

My last post really was the conundrum of how to balance a memory with the pragmatic logistics of a space. It was brought up by a group's visit to a concentration camp where they were admonished by staff not to sing a melody once sung by those murdered there.

4 weeks ago I left for a 2 week trip to Germany with the above question in mind. Once there I came to realize the question was a microcosm for what we, Jews, Germans, the world is really asking...How should we remember the Holocaust?

It's a question I had never truly considered before. Obviously terrible, obviously tragic, obviously so painful to even write this. But how do we remember? How should we? What should we do? From memorials to education to prevention- how?

I traveled through Berlin, Wolfsburg, Nuremburg and Munich with a German program in affiliation with the Orthodox Union. The first night I could not fall asleep. It was one part jet lag and three parts an avid imagination fraught with images of the Jews who had walked Swedter Strase (street) before me. I had been keen on experiencing the second hand culture of Berlin, especially after my luggage failed to arrive, but when I finally got to a thrift store the realization that some things may be circa 1930's made me freeze. As did a menorah in an antique shop. Germany is permeated with ghosts that the living are trying to find a way to live alongside.

The "Stolperstein" are gold cobblestones with the names of Nazi victims placed on the ground outside the home where they had lived. German residents commission them on their own. One is supposed to "stumble" and remember. It is a gesture of acknowledgement of the past. Not all like it as Jewish names are stepped on. Some would have preferred the extra euros to be spent by placing it near the doorbell.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe are plain slabs of concrete in a centrally located square in Berlin. The heights of the stone ranges and there are over 2,000. The lack of symbolism is supposedly meant to allow one to create their own feelings of remembrance. The orderliness of the stones is jarred by their varying heights.

Are slabs of concrete the way to memorialize? Another participant noted it did not touch his emotions. Perhaps if one were to wonder and ponder then one would react to the site. Children frolicked and jumped over the stones and people used the slabs as picnic benches. Was it not solemn enough? Respectful? Or was it a victory to frolic and dine where we once could not? Does it negate being solemn?

I had never heard of the "Block der Frauen" memorial to the German women who had demanded the release of their Jewish husbands. I had never heard the story. I wonder if it was because of the intermarriage or if it was omitted due to the sheer volume of memories. How shall we educate? What shall we choose to tell?

Beneath the vast memorial is a Holocaust Museum. One comes from the outside with a gentle, general reminder of the Holocaust as a whole to an anguished exhibit where it becomes wretchedly personal. Postcards and letters rising with terror as those who realized what was happening wrote goodbye to "mon cherie." The most terrible is the family trees telling of what happened to each family.

There was one picture of a Zaidy helping his grandchild walk. Another of parents with a delightful rolly polly baby. It could G-d forbid have been a cousin, a niece, a nephew. For me it was the worst of all the memorials because I thought of my nephews and nieces. The ones I love so much. It makes my heart ache.

Does one take pictures at a concentration camp? Does one pose? Does one smile? Should pictures not be taken at all? It is hard to study modern Germany when one is not sure of how to behave while doing so. Here unlike the memorial is where people were actually murdered. Should one smile at a grave? Can we ask our guide questions about life in the concentration camp or should we be in a stupor of repulsion?

4 weeks ago I left for a 2 week trip to Germany with the above question in mind. Once there I came to realize the question was a microcosm for what we, Jews, Germans, the world is really asking...How should we remember the Holocaust?

It's a question I had never truly considered before. Obviously terrible, obviously tragic, obviously so painful to even write this. But how do we remember? How should we? What should we do? From memorials to education to prevention- how?

I traveled through Berlin, Wolfsburg, Nuremburg and Munich with a German program in affiliation with the Orthodox Union. The first night I could not fall asleep. It was one part jet lag and three parts an avid imagination fraught with images of the Jews who had walked Swedter Strase (street) before me. I had been keen on experiencing the second hand culture of Berlin, especially after my luggage failed to arrive, but when I finally got to a thrift store the realization that some things may be circa 1930's made me freeze. As did a menorah in an antique shop. Germany is permeated with ghosts that the living are trying to find a way to live alongside.

The "Stolperstein" are gold cobblestones with the names of Nazi victims placed on the ground outside the home where they had lived. German residents commission them on their own. One is supposed to "stumble" and remember. It is a gesture of acknowledgement of the past. Not all like it as Jewish names are stepped on. Some would have preferred the extra euros to be spent by placing it near the doorbell.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe are plain slabs of concrete in a centrally located square in Berlin. The heights of the stone ranges and there are over 2,000. The lack of symbolism is supposedly meant to allow one to create their own feelings of remembrance. The orderliness of the stones is jarred by their varying heights.

Are slabs of concrete the way to memorialize? Another participant noted it did not touch his emotions. Perhaps if one were to wonder and ponder then one would react to the site. Children frolicked and jumped over the stones and people used the slabs as picnic benches. Was it not solemn enough? Respectful? Or was it a victory to frolic and dine where we once could not? Does it negate being solemn?

I had never heard of the "Block der Frauen" memorial to the German women who had demanded the release of their Jewish husbands. I had never heard the story. I wonder if it was because of the intermarriage or if it was omitted due to the sheer volume of memories. How shall we educate? What shall we choose to tell?

Beneath the vast memorial is a Holocaust Museum. One comes from the outside with a gentle, general reminder of the Holocaust as a whole to an anguished exhibit where it becomes wretchedly personal. Postcards and letters rising with terror as those who realized what was happening wrote goodbye to "mon cherie." The most terrible is the family trees telling of what happened to each family.

There was one picture of a Zaidy helping his grandchild walk. Another of parents with a delightful rolly polly baby. It could G-d forbid have been a cousin, a niece, a nephew. For me it was the worst of all the memorials because I thought of my nephews and nieces. The ones I love so much. It makes my heart ache.

Does one take pictures at a concentration camp? Does one pose? Does one smile? Should pictures not be taken at all? It is hard to study modern Germany when one is not sure of how to behave while doing so. Here unlike the memorial is where people were actually murdered. Should one smile at a grave? Can we ask our guide questions about life in the concentration camp or should we be in a stupor of repulsion?

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

On the Conflation Between a Museum Visit and a Soul Journey

I interned at a non-sectarian museum this year. The word ‘non-sectarian’ came up in the interview and I pretended I knew what it meant or I asked. Whichever. According to Google it means:

1. not involving or relating to a specific religious sect or political group.

This made sense as the museum is non-sectarian and partially publicly funded. It is a culturally Jewish institution with no religious, or little religious, merit. However the museum is culturally, architecturally and historically significant. What is this museum you ask? It’s a 19th century synagogue.

The catch is that it still functions as a synagogue today. The museum closes shop Friday afternoon and Saturday and the few remaining congregants move in for the Shabbat.

Now the museum staff and synagogue board have an complex relationship. From what I understand, the synagogue technically owns the building but the museum covers all the maintenance expenses. What’s more the museum is a result of a $18 million project that restored the dilapidated space and is the reason it is still standing. In other words if not for the project which led to the museum there would not be a synagogue.

The prevailing attitude of the congregation is that they deem to acquiesce that the museum be there. Which is ironic as there would be no building without the museum as upkeep of the synagogue dwindled as the Jewish population in the area dwindled.

The museum staff refer to “space” as a construct to describe the building’s importance in both American Jewish history and in the present as well as immigrant life today. Yet, there is something that bypasses the rhetoric of a ‘space.’ This space is a synagogue.

My high school was in a converted Jewish center first built in the 1940’s or 1960’s. On the ground level there was a synagogue which was also a shortcut to the second story of the annexed building. Slight issue: according to Jewish tradition, it is inappropriate to use a holy synagogue as a means of getting somewhere faster. The loophole is saying a verse Torah as you walk.

When I walk into the museum, ergo walk into the sanctuary, I quietly whisper a verse of Torah. Though I am there for the museum, what the space is, non-sectarian vernacular or not, is a Jewish house of worship. It would be so whether it was in use or was not.

August of this year Rabbi Rafi Ostroff led a group on a visit Auschwitz. Let’s forget for the moment that there is a fee to enter this place which I personally feel should fall to pieces or at least not be so magnificently maintained. The visit resulted with him being given the ultimatum of spending Friday night in jail aka Shabbat or paying a fine of $300.

Let’s look at some of these articles:

His group of teenagers sang the song of Ani Mammin, a song about faith that was sung by the Jews being led to the gas chambers. The guards ordered them to stop which they did not.

"Ostroff said that in a “secluded part” of the Birkenau camp, the “boys spontaneously started singing ‘Ani Maamin.’ This was the song that prisoners sang on the way to be murdered there. A guard drove after us with his car and demanded that they be silent. I told him that I don’t have control over this as they are singing from their hearts. He then threatened to arrest me and called the police.”"

Read more: http://www.jta.org/2014/08/04/news-opinion/world/israeli-rabbi-demanding-apology-after-group-prevented-from-singing-at-auschwitz#ixzz39aMRLHsj

Read more: http://www.jta.org/2014/08/04/news-opinion/world/israeli-rabbi-demanding-apology-after-group-prevented-from-singing-at-auschwitz#ixzz39aMRLHsj

Why were they not allowed to sing? The guards said because it was they were disrupting other visitors and instructors. Fine. I’ll accept that. But this is what I will not accept:

"Danny Feigen, a student at Yeshivat Eretz Hatzvi in Jerusalem and member of Rabbi Ostroff’s group, witnessed a guard ask, “would you sing in the British museum?” "

And that is where the truth is lost. These places are not museums. They are witnesses to Jewish life. Some of the teenagers in the group had family who died at Auschwitz. Visiting these places are not due to impartial curiosity of the culturally, architecturally or historically significant.

These so called “spaces” are not just ideas inhabiting a place. As Rabbi Ostroff said, “It is a journey to the depths of our souls.”

An elderly Jewish man visited the museum and he broke out in a Jewish song. Credit goes to the museum staff for grinning and bearing it.

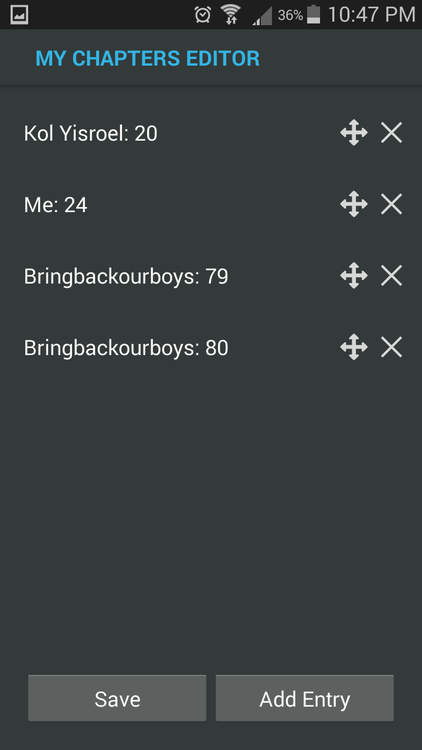

My S3 Memorial #bringbackourboys

The day the boys were declared dead was also the day I made a shortcut for the psalms assigned to me (to pray) on my phone. The shortcut was not a pessimistic presumption that we would not find them quickly but a way of ensuring I would not forget to do my part.

I named the shortcuts #bringbackourboys. I went to a rally. I prayed. I freaked out because my sister was on Birthright though I warned her not to get into random carsand not to hitchhike even before this happened.

I was awed by the faith and courage of Eyal, Gilad and Naftali’s families. I was blown by the unity of people both Jewish and not. My inner Jewess, demonstrator, lover of the Holy Land, protester was unleashed.

Then their bodies were found. I was shocked. I had not expected it. I had been awaiting a miracle.

Other things happen. Some pleasant.

A nasty person made up a story of a couple renaming their triplets after the boys and I stopped sharing articles on facebook without running them by Snopes.com.

A couple actually, really, truly did name their son after the 3 boys. They were inspired by the unity these boys ignited. That was loaded. I applauded them but could not imagine doing the same.

The IDF moved in and the tunnels were uncovered.

Through it all my finger hovered over that #bringbackourboys psalm shortcut. After all we were no longer splitting the psalms. It was time to delete it.

In a rush I was overwhelmed by the unity I had felt. That though the initial reason for this shortcut was not there something that surpassed that reason still was. The feelings expressed and lessons learnt were still there.

So I kept the shortcut and I try to say the psalms.

They are there as a testimonial. As a memorial. As a daily reminder of Israel and of our spirit. And as an everlasting tribute in the form of prayer for Eyal, Gilad and Naftali -may they rest in peace.

Freshman Flashback: Day 1

As per usual I was hyper aware, my nerves fully charged as I selected a seat toward the back in my Comp 1 class.

People filed in and then the professor came in. A very tall, rail thin, lanky woman with cropped brown hair, many ear piercings, a short skirt, sleeveless shirt and glasses. She happened to look exactly like my eleventh and twelfth grade English teacher.

Which wasn’t a possibility as my English teacher at my Bais Yaakov type school was orthodox and had a short blonde wig. She did not have numerous piercings and wore orthodox-modest long skirts. I had found her doppelganger. This was unfortunate. My English teacher had accused me of plagiarizing a line from a paper on A Separate Peace. I found this insulting, not because of the implications on my moral character, but because of the implication that I needed to cheat.

The resemblance was eerie. And then in struck me. The professor’s name was my high school teacher’s maiden name. I nugget of information I had forgotten. They were sisters. Duh.

After class I pushed aside my anxiety of college and of talking to people and approached my professor to ask, “Do you know a Mrs. R?”

She gave me a look and replied, “I am Mrs. R.”

So, being a realist, I took this to mean I would not leave college still orthodox. Like her if I would drift astray from Torah path under the influence of college. The rabbis and teachers at my high school had given dire warnings of such things.

My anxiety reached overdrive. Should I stay in college? Should I not?

I took three classes that semester. I earned an A, A+ and a B.

That ‘B’ would be the only grade under an A- that I would earn at college.

I know my work was not up to par but I always wondered if there was some sort of pyschological reason I could not conquer that class.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)